Fatwood: What It Is, How to Find It, and Why It’s a Top Natural Firestarter

When it comes to lighting fires in the wild, especially in damp or windy conditions, few natural materials are as reliable as fatwood. Rich in natural resin, fatwood burns hot with a long-lasting flame. Fatwood is a material that, once you’ve learned how to use it effectively, secures a permanent place in your list of essential bushcraft and survival resources.

In this article, I’ll explain what fatwood is, where to find it, what it is used for, and how to use it effectively. I’ll share my experiences with harvesting fatwood and using it in the field. I’ll also explain how to make small, highly flammable feather sticks from it. There is an embedded video demonstration to go with this. If you’re serious about mastering fire lighting outdoors, understanding fatwood is essential.

What is Fatwood?

Fatwood is the resin-saturated heartwood located in certain coniferous trees, particularly pines. It forms when pine resin collects in a stump and roots, or at old branch junctions. This formation often occurs after the tree dies, suffers damage, or someone fells it. Over time, the resin concentrates in the remaining wood. Fatwood is also found in the heartwood of some old-growth pine trees.

How to Identify Fatwood

It is a dense, golden-orange or reddish-brown material. It feels much heavier than regular, seasoned pine. If fresh, it can be sticky to the touch; if older, it becomes hard and non-sticky. As the sap-soaked wood seasons, terpenes in the sap evaporate over time, leaving a solidified resin. Fatwood emits a distinctive scent of pine, particularly when shaved or cut.

Other names for fatwood include “lighter wood”, “lighter knot”, “pitch pine”, “resinwood”, or “fat lighter”. As some of these names suggest, people prize fatwood for its flammability. Even after this resin-heavy wood is exposed to moisture, it ignites with little effort. Resin repels water, so unless the wood fibres have absorbed a significant amount of moisture, fatwood will not contain much fire-dampening moisture.

The high resin content of fatwood contributes to its strong resistance to rot. The resin also burns very well, resulting in a sustained, intense flame when the resin-infused wood is used. Once burning, it is difficult to extinguish, even in windy conditions. These properties make it an ideal natural firelighter in bushcraft and survival situations. It’s also harvested and sold as a firelighter and barbecue charcoal lighter.

Where to Find Fatwood

So, what trees have fatwood? Well, fatwood doesn’t form in every conifer, nor in every part of a tree. But it is usually found in parts of a suitable tree where resin has pooled and hardened. These areas are usually found at the base of dead stumps, at the junctions where large limbs connected to the trunk, or in sections of trunk from old-growth or long-dead standing trees.

Which Tree Species Have Fatwood?

Knowing how to find this material involves some tree identification. Pines (genus Pinus) are the conifer most associated with fatwood. All pines can produce it, so always be on the lookout in pine forests. Historically, some particularly resinous pines became known for their high pitch production. These trees have also offered valuable sources of fatwood, especially for commercial harvesting.

What are the Best Trees For Fatwood?

In the southeastern USA, the species commonly associated with fatwood is Pinus palustris, known as the longleaf pine. Following a period of heavy felling of this species for lumber, many stumps remained.

In Mexico, Montezuma pine, Pinus montezumae, is a source of fatwood. This pine is one of multiple pine species native to Mexico and Central America, known as ocote, a term in Mexican Spanish. This word originates from the Nahuatl word ocotl, meaning “torch”. Indeed, ocote also refers to the highly flammable, resin-infused wood sourced from these trees, otherwise known as fatwood.

Scots Pine, Pinus sylvestris, is a significant source of fatwood in its native range across Eurasia, from Scotland to the Russian Far East.

Where to Find Fatwood Trees (Pines)?

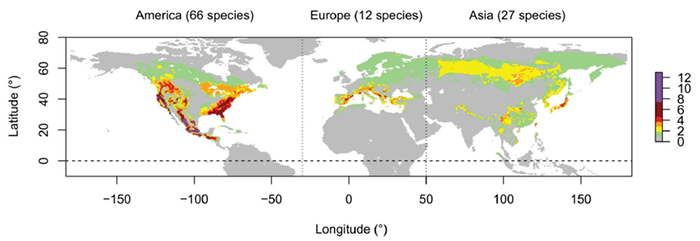

Pines are a predominantly Northern Hemisphere genus of around 110-120 species. Despite not being a huge genus, when you are north of the equator you’ll encounter pines in nearly any terrestrial habitat type that supports trees. Furthermore, humans have introduced pines to many non-native habitats in the Southern Hemisphere. The pines are a widely distributed and commonly found set of species. Hence, we stand a good chance of encountering the resources pines can provide, including pine fatwood.

separated by meridians at 30◦W and 50◦E – named America, Europe and Asia for simplicity.

The above disribution map is credited to Nobis, Michael & Traiser, Christopher & Roth-Nebelsick, Anita. (2012). Latitudinal variation in morphological traits of the genus Pinus and its relation to environmental and phylogenetic signals. Plant Ecology & Diversity – PLANT ECOL DIVERS. 10.1080/17550874.2012.687501.

Finding Fatwood in Tree Trunks

Some of the richest fatwood is found deep in the trunks of dead-standing pine trees. In these cases, the heartwood has become saturated with resin over time. The wood from these trees can be dense and challenging to harvest by hand. While there might be a rich seam of material here, it’s not what you are going to target for small amounts of immediately usable fire-lighting sticks while on a backwoods trip.

Harvesting Fatwood from Tree Stumps

The remains of pine stumps often hold concentrated resin-infused wood in the heartwood. Even if the surrounding stump appears weathered, the core can be solid and rich in resin. By chipping into the top of the stump with an axe, you can expose this dense material. Fatwood is denser, heavier, and darker in colour than decayed softwood. Once removed from a tree stump, one can split chunks of fatwood into smaller sticks or splints.

How to Harvest Fatwood from Dead Branches

One accessible source of fatwood is the dead branches of pine trees, especially lower limbs that have dried out and retained their resin. When sourcing this, look for wood that is darker than the surrounding branch material, often with a rich amber or orange colour inside when cut. If you shave a piece and it has a strong pine scent and an oily or sticky texture, you’re on the right track.

Why Does Fatwood Burn So Well?

Fatwood’s effectiveness lies in its high resin content. Pine resin is a hydrocarbon-rich substance that ignites readily and burns at a high temperature. These flammable constituents mean you can easily light fatwood with a small flame, even with a ferro rod spark when properly prepared.

Resin also repels water, so fatwood remains usable even when other tinder and kindling are damp. It can be a game changer in wet weather, when you need to get a fire going quickly and reliably.

Once you have some of this natural firelighting material, you need to know how to start a fire with fatwood…

How to Use Fatwood for Firelighting

There are several effective ways to use fatwood in fire-lighting. The choice you make depends on the situation, your tools, and the amount of fatwood available.

Making Fatwood Scrapings or Dust for Ferro Rods

Create a pile of fine material using the spine of your knife or saw, or the knife edge, scraping at right angles against a stick of fatwood, preferably on a sharp-angled edge. The scraped dust will catch a spark from a ferro rod. You don’t need to use up too much of a fatwood stick to create a pile of dust that will ignite. This technique is advantageous in unchallenging conditions when you want to achieve quick ignition from a ferro rod spark to get some small sticks burning.

Click here to learn more about the best ferro rods.

Shavings: Preparing Fatwood for Easy Ignition

Thin, curly slivers of fatwood take a little more work than scrapings/dust. But these work well for fire-lighting when you need a bit more initial flame. Shavings introduce more flammable material than dust. A pile of shavings will contain more oxygen in and around it compared to a compact pile of fatwood dust. Use a knife to shave thin slivers of fatwood. These will light easily from a small flame, such as a match. If the slivers are fine enough, they will light with a spark from a ferro rod.

Making Fatwood Feathersticks

Making feathersticks from this resin-rich wood takes the fatwood-shaving idea one stage further. Here you still make shavings, but with a feather stick, (most of) the shavings stay attached to the stick. Feather sticks made from fatwood are ideal for creating an intense flame that ignites quickly and sustains itself long enough to ignite other kindling.

You can ignite fatwood feather sticks with matches, lighters, or ferro rods. Like feather sticks made of other wood types, you can move fatwood feather sticks once they are lit. This is not something you can accomplish with a pile of fatwood shavings or dust. You can light the feather stick in a place that is convenient for you to drop a spark from your ferro rod. Then, move the feather stick to bring the flame to your kindling or fire lay that’s already set up. Watch the video below for more details.

Watch: How to Make Feathersticks from Fatwood

In this video, I show how to make small, effective feathersticks using pieces of fatwood. These feathersticks burn hotter and longer than those of a similar size made from non-resinous softwood. This extended burn time and high heat give you a better chance of fire-lighting success in damp conditions. It also works to introduce enough heat energy to ignite larger sticks than the fine kindling required to establish a fire from a smaller flame.

Is Fatwood the Best Natural Firestarter?

Fatwood is one of nature’s best fire-starting materials. This fire lighter is produced naturally by a set of species – the pines – that is common and widespread. It’s easy to carry, lasts a long time, is easy to prepare, and performs in conditions where other tinder and kindling sources fail.

A few sticks of fatwood in your fire kit as an emergency backstop can make the difference between success and failure.

You can even buy fatwood on Amazon. Yet, I’d always recommend that students of bushcraft learn to identify, collect, and use fatwood in the field.

A note on harvesting: Ensure you source fatwood in an ethical and responsible manner. Only take wood from dead trees or fallen limbs. Never cut into green wood (live wood) to try to access this material.

How To Store Fatwood

Once you have some fatwood and understand it is such a valuable fire-lighting resource, a natural question is How long does fatwood last? Does it degrade? Does it lose potency?

You’ll be glad to read that this resin-soaked wood is durable and lasts a long time due to its high resin content. Unlike some other forms of kindling, it resists both moisture ingress and decay, which makes it easy to store over long periods. Fatwood is robust; sticks and splints made of it resist crushing or snapping.

You can carry collected pieces of fatwood in your pack. You can store prepared small fatwood sticks in a metal box or alongside your other fire-lighting kit. You can bundle and stash them in the pocket of your pack or in a possible pouch, for example. Some people even carry a chunky stick of fatwood with a lanyard hole drilled into it and carry it along with their ferro rod.

There is no special preparation needed. This material does not readily deteriorate, and its ignition qualities remain reliable even after years in storage. Moreover, resin-infused pine is so rot-resistant that collectors have gathered perfect fatwood from tree stumps many decades after the tree was felled.

Want to Learn More?

If you’d like to improve your ability to light fires in the wild, regardless of the weather, then check out my Fire Essentials: Mini Masterclass.

🔥 In this concise online training, I walk you through the key techniques, materials, and methods that I use and teach on my wilderness skills courses. Whether you’re new to fire-lighting or want to deepen your knowledge, this mini masterclass will give you a solid foundation.

Related Fire-lighting Material On This Website

Lighting a Fire With Feathersticks

5 thoughts on “Fatwood: What It Is, How to Find It, and Why It’s a Top Natural Firestarter”

Fatwood is a neglected treasure which we seem to forget. Glad you brought it into the limelight and to our awareness (again).

Being raised in rural Canada, in the 1960’s, we heated our home with wood. We had cold running water only, which was better than my grandfather down the road, who sourced his water from a spring on the mountain side. But we had the wisdom of the elders. I grew up taking for granted the luxuries of birch bark and fatwood, and assumed it was common knowledge. When we chopped our firewood, we set aside the fatwood laden pieces for kindling, knowing they would ignite that stove easily on winter days of 40 below (Celcius or Fahrenheit, it don’t matter), and the house would warm up after a cold early morning. And now, in my old age, I see a resurgence of this knowledge being taught to people who have never seen the likes of it. Life is indeed a circle, isn’t it?

We are a small people, few and far between, in a world of push buttons and central heating.

Hi Paul… With a few exceptions, I add a 550 cord lanyard (through a small, drilled hole), onto my fatwood sticks, (and ferro rods), that is slightly longer than the stick so that it can be looped through to attach it to my belt, pack etc . This positions my fire starting gear were it is immediately available without getting into the pack.

Hi Mike,

Thanks for sharing your set-up, which makes perfect sense.

In case you haven’t seen it, I think you will find the following article (and video) interesting:

https://paulkirtley.co.uk/2024/optimise-ferro-rod-pocket-carry/

Warm regards,

Paul

Hi Paul, here in Maine, usa, fat wood is not as abundant as other areas, yet I can find it in dead branches of both white pine and black spruce, right at the base of the branch next to the trunk, there is often but not always, a thin 1/8″ ring around the branch, very rich stuff and its my go to for fire starting, I prefer it over birch bark for wet conditions.